Uncategorized

Terry Clock Company

The clock at the top of its tower did more than just announce the time of day. It was a suitable advertisement for the new innovative clock that was produced in the four stories of this commanding structure not far from the train station and the city center. Eli Terry expanded his clock company north from Connecticut to Pittsfield in 1883 for its special brand of clocks that could receive and send telephone signals, developed by Pittsfield resident George H. Bliss. At its peak, the company produced 150 different styles of clocks, employing 120 people with a daily output of 350 clocks. Its peak did not last long, though, as investors who owned the Russell Woolen Mill bought the clock company from Terry and changed its name.

Then, just ten years after it was built, the Terry Clock Building was sold and converted for use as a paper manufacturing plant for the Hurlbut Stationery Company. Its President, Arthur W. Eaton turned around and bought the company in 1899 and expanded its operations under a reorganized company bearing his name. First, it was Eaton-Hurlbut and then Eaton, Crane and Pike. With 450 employees, the company produced both the fine writing paper, the envelopes and the sturdy, elegant boxes holding both. In 1916, Eaton, Crane and Pike produced 1.5 million sheets of stationery and sold them across the country and in Europe and Latin America. The company continued to expand and acquired at least one of the old Pomeroy Woolen Mill buildings nearby.

It seemed only logical that a stationery company would find its next partner in a pen company, and in 1976 the merger between Sheaffer pens and Eaton paper was finalized. Sheaffer-Eaton became the second largest employer in the city, hiring up to 900, with about two-thirds of its workforce women. By 1987, though, just as General Electric was closing its operations, Sheaffer-Eaton was sold and the owner of the Berkshire Eagle, Lawrence Miller, bought the building. In 1990, the same year that the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Berkshire Eagle moved its operations to a newly renovated building that housed its new color presses and additional office and residential space.

Robbins and Kellogg Shoes

What would it take to produce 1800 pairs of shoes a day in the late 1800s? Employing around 450 workers to operate leather cutting, stitchers, lasting (or shaping) machines and over 100 sewing machines, Robbins and Kellogg sold its shoes across the country. Established in 1870, the factory used a 40 horse power engine powered by coal.

Built in 1870, the shoe company only lasted for 30 years. By 1900, Pittsfield’s electrical industry had taken off, and these factories were re-adapted at first for companies producing equipment for General Electric. Later, it became a warehouse for GE and then for England Brothers, Pittsfield’s premier department store located on North Street.

Situated in the middle of the city, the factory is surrounded by housing for its workers.

A large four story, brick building, dormers protruding from the roof bring light into the attic and give it additional warehouse space. Passing by, check out the cornice designs where the roof meets the brick facades and the fading “Warehouse” lettering on the side of the building.

Pontoosuc Woolen Mill

At the height of its manufacturing success, more than 400 men, women and children crossed the bridge over the headwaters of the Housatonic River to head to work at the Pontoosuc Woolen Mill. They produced woolen blankets for carriages and for soldiers in World War I and fashionable balmoral dresses for women throughout the 19th century.

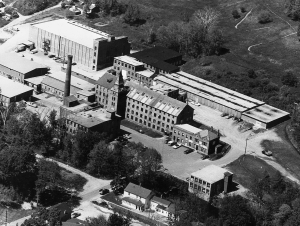

This was not only the longest operating woolen mill in the city, but also the largest complex, consisting in 1926 of over 25 different buildings, including worker and manager homes, a store, a boarding house, warehouses, boiler rooms and main buildings for the carding, spinning, weaving and dyeing functions. Its main building housed a water wheel in its basement, drawing power off a canal diverted from the river, and 4 floors of carding, weaving and dyeing rooms. Originally constructed in 1826, the mill took over the site of Keeler’s saw and grist mill to take advantage of its dam at the southern end of Pontoosuc Lake.

Its unique features include its bell tower/staircase with a multi-colored slate roof and the raised decorative friezes at the corners of the gables on Building A. An elevated walkway between the main buildings and the rear warehouse was torn down.

Worker and owner houses bordered the mill, as well as a store and a trolley opened in the 1870s to transport workers from the center of Pittsfield to the mill in the north of town.

Shortly after its 100th anniversary, ownership transferred to Wyandotte Mills of Maine. Wyandotte ran the mill until 1963, the last of its kind in Pittsfield. Today, it is an industrial park, housing small businesses with its large buildings perfect for warehouses.

A.H. Rice Silk Mill

Forty years after the closing of Pittsfield’s woolen mills, one textile mill stayed in operation – the Rice Silk Mill on Spring Street. Its origins, though, were in the woolen industry, starting out in 1876 as the Farnham and Lathers Woolen Mill. Perhaps it was the competition of 11 other mills in the city or just another of the recurring recessions in the late 1800s, but, by 1887, the wool company had failed. William B. and Arthur H. Rice bought the complex for $3800 for their mill that they had started at the corner of Linden Street and Robbins Avenue. Here they produced the finest of textiles – silk and mohair.

Three adjoining brick buildings housed the offices, storage and the different operations for the silk, including spinning, braiding, finishing and dyeing. A braid mill for the mohair took up a fourth, separate building. Launching after the Civil War meant that the mill was not reliant on water power, and therefore did not have to abut any of the city’s rivers. Its power came from a coal-fired steam plant.

The plant grew fast, with employment expanding from 125 operatives in the 1890s to 250 in 1915. Its reputation for fine, unique thread and braids products also grew, and earned a distinctive name for its line – the Rice Braid. Its products were sold for uniforms – government and commercial – worldwide. The Rice family owned and operated the company into the 1980s when it sold to a New York firm that had supplied it with its silk fiber for years.

Subsequent owners operated the factory until 2006 when it closed and let go the remaining 100 employees at the facility, moving its operation to South Carolina. ELC Industries bought the company and continues to produce its Rice Braid, crediting its A.H. Rice forebears.

The complex at the corner of Spring and Burbank Streets only lay vacant for several years. After a series of complex negotiations, the mill buildings were converted in 2012 to residential apartments operated by Berkshire Housing Services at a price tag of $15 million, the bulk of which came from the Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development.

The Mills of Pittsfield

They dot our landscape, in plain view, but at the same time are hidden from our current preoccupations and distractions. They belong to the 19th century but continue to shape Pittsfield in the 21st century. They are the factories that drove the economy, the mansions and city institutions built by the civic-minded owners and managers of the mills and the mill houses of thousands of workers and their families who came in search of a better life.

Take a step back in time and take a tour to find the buildings that are our history. Read about their origins and our ancestors who worked in them. Examine how the strength of structure and beauty of design continue to serve the city and its people as apartments, workplaces and warehouses. a variety of uses in the city.

Your photographs and memories are welcome to complete the story. The patterns of brick, the features of tile roofs and bell towers and railings, the lines of porches and verandas in the changing Berkshire seasons and sunlight all lend themselves to photographic compositions.

- ← Previous

- 1

- 2

- 3